|

Adam Tanaka

JCHS Meyer Fellow |

This post is cross posted from a series that our

colleagues at the Ash Center for

Democratic Governance and Innovation are doing on affordable housing

as a challenge to the health of American democracy, and in particular local democracy

in the United States. The series, edited by Harvard Kennedy School Assistant

Professor Quinton Mayne, is part of the Ash Center’s Challenges to Democracy series,

a two-year public dialogue inviting leaders in thought and practice to name our

greatest challenges and explore promising solutions.

As part of this series, Adam Tanaka explored the ways in which housing shortages in expensive global cities

are leading to a redefinition of affordability, both for low- and middle-income

residents. Population and productivity growth, coupled with increasing income

inequality, is contributing to a pressure-cooker housing market in which supply

is falling far short of demand. As a result, public authorities are finding new

ways to partner with private developers to try and meet demand for below-market

housing. Tanaka sat down with private developers who are playing an important

and telling role in the delivery and management of affordable housing.

For this interview in the series, Tanaka

traveled to New York City to interview Rick Gropper of L+M Development

Partners, a private affordable housing development company with thirty years of

experience in New York. Their conversation reveals some of the political

challenges still facing developers operating in this field, as well as new

opportunities for innovation across the public-private divide.

New York City has a long tradition of innovation in affordable housing. From

building the country’s

first

public housing project, to establishing its

longest-running

program of rent control, to experimenting with tax credits that influenced

the adoption of the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit, the city has a

strong legacy of public intervention in the housing market.

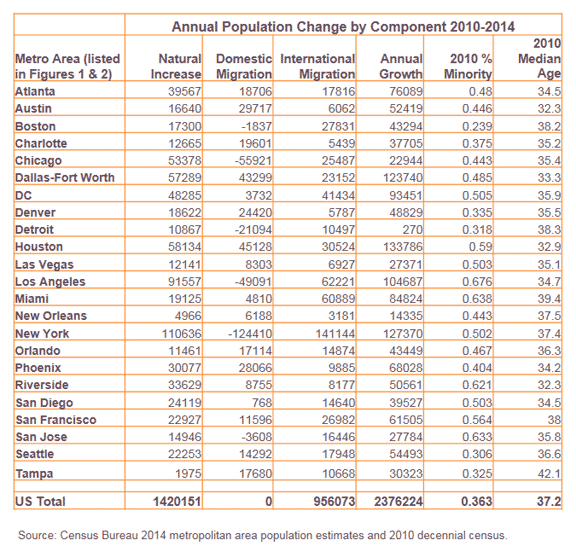

New York cannot rest on its laurels, however, as a number of trends continue

to threaten the city’s affordability. Most obviously, the city’s population is

growing, adding considerable stress to the housing stock. Following dramatic

population decline and widespread abandonment in the 1970s, the city has

rebounded,

reaching

an all-time high of 8.5 million residents in 2014. The city’s housing

market, however, has failed to keep pace, with a shortage of new development

driving up housing costs to the point that the median sales price of a home in

Manhattan is

just

shy of $1 million. A surge in foreign investment has added further stress

to the system, as a growing number of condominiums sit empty, purchased as

assets rather than homes. As the real estate market surges, the “funding gap”

between market and affordable rents grows, requiring ever larger subsidies to

develop new affordable homes.

In theory, the city’s

existing affordable housing stock is supposed

to be unaffected by these market trends. Programs like public housing, rent

control, and Section 8 vouchers were purpose-built to protect low-income

families from a housing market out of their reach, providing long-term

affordability through a variety of methods. In reality, however, a number of

programmatic impediments have begun to erode the city’s affordable housing

stock. This includes the

expiration

of affordability requirements for many housing developments built in the

1970s and 1980s as well as the removal of units from rent regulation through a

technicality known as

“luxury

decontrol.” It is estimated that over the course of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s

first term in office,

45,000

housing units will exit affordability, allowing landlords to charge

market-rate rents for the first time if no new subsidies are put in place.

Even public housing—owned and operated by the public sector and thus

theoretically the most secure form of affordable housing—is threatened by an

increasing lack of federal money for both daily operations and long-overdue

capital improvements. As the country’s largest housing authority, the New York

City Housing Authority (NYCHA) has been particularly hard-hit by this federal

shortfall. In 2014, the agency suffered from

a

$77 million budget deficit and had estimated capital needs totaling $18 billion,

mostly in structural improvements to buildings, many of which are over fifty

years old. As such, NYCHA officials are actively exploring new ways to generate

revenues for the agency and close the funding gap. One strategy is to

lease

under-utilized land adjacent to public housing to private developers for new

construction. Another is to restructure the funding for public housing to

tap new federal sources such as the

Rental Assistance

Demonstration program.

A third method, which this interview explores in detail, involves the

Housing Authority partnering with for-profit developers to access both private

capital and federal funds only available to private applicants. In February

2015, NYCHA formed a public-private partnership with two private development

companies, L+M Development Partners and BFC Partners, to revitalize a

particularly distressed subset of its portfolio: six project-based Section 8

developments housing over 2,000 residents across the Bronx, Manhattan, and

Brooklyn. The project-based Section 8 program, initiated in the early 1970s by

the Nixon administration, was an operating subsidy mostly intended for use by

private developers. However, a number of Section 8 developments fell into the

housing authority’s portfolio during the city’s fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s,

when NYCHA was better capitalized than the city itself.

Queensbridge Houses, largest public housing development in US (source).

Now that this situation has reversed, NYCHA is exploring new ways to

generate revenues not only for its Section 8 projects, but also for its general

portfolio. Transferring 50% ownership of these developments to private hands

opens the door to tax-exempt bond financing and tax credits, sources generally

unavailable to housing authorities. The private partners, meanwhile, benefit

from Mark-Up-To-Market contracts from the Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD), which compensate landlords for the difference between 30% of

tenant incomes and market rents.

Of course, even this partial privatization of public housing has generated

substantial controversy amongst tenants, local politicians, and housing

advocates. To learn more about the politics behind this proposed deal, the Ash

Center spoke to Rick Gropper at L+M Development Partners. One of the city’s

foremost private affordable housing development companies, L+M’s evolution over

the past thirty years epitomizes the growing professionalization of the sector

as a whole. The conversation with Gropper reveals some of the political

challenges still facing developers operating in this field, as well as new

opportunities for innovation across the public-private divide.

Adam Tanaka: Could you describe L+M’s position within the affordable

housing landscape in New York City?

Rick Gropper: L+M has been around for about thirty years. The first projects

that we did were under the Vacant Building Program, where the city acquired

buildings that were in tax foreclosure. These buildings were vacant, and many

of them were shells. The city then transferred them to private developers for a

dollar. Prospective owners would bid down the rents. One would say: “I can do

this job and I’ll charge the residents $500 a month.” Another would say: “I can

do $450 a month.” Whoever came up with the financial structure that charged the

least rent would get the building.

Then the Tax Act of 1986 introduced a new financial mechanism, the Low

Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). The founders of L+M figured out how to

syndicate tax credits and place tax-exempt bonds, and they used that financing

to charge residents even less for rent. That was the genesis of L+M, working

with city and state agencies to gut-renovate buildings across the city.

As the affordable housing industry matured, the company moved to new

construction, working with the city to subsidize projects on city-owned land.

The city had a lot of land because they had demolished buildings for a variety

of reasons. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development, the city’s

housing agency, would offer different development sites for a dollar, and would

then work with the developer to figure out how to finance them, whether it’s

tax-exempt bonds or tax credits or subsidy, or some combination of all three.

From the mid-1990s until today, L+M has been predominantly a developer of new

affordable housing. We’ve slowly gotten into some other things, such as new

construction of market-rate buildings, but most of our work is affordable

housing.

There’s been a lot of media attention recently on the expiration of

various affordable housing programs. Has L+M been involved in the refinancing

of housing developments to enhance their affordability?

Five or six years ago, a lot of the housing stock that was developed in the

late 1980s and early 1990s hit what’s known as the “Year 15,” which is the end

of the tax credit compliance period. When you’re working with Low Income

Housing Tax Credits, they’re delivered to the owner over a 10-year period, and

there’s a 15-year compliance period. Once that compliance period ends, you can

actually re-syndicate the tax credit properties. When you re-syndicate, you

extend the affordability for another 15 years. We have worked to extend

affordability in a number of areas facing market pressures, such as Harlem, the

East Village, Bushwick and Clinton Hill. When you re-syndicate a building, you

might put $40,000 into a unit for renovation, replacing roofs, common areas,

boilers, systems and technology changes over time. Being able to re-syndicate

and renovate is really important.

What factors do you think drove the city to start relying on the

private sector for affordable housing?

For a long time, the city used to build and finance new housing. That ended

in the 1970s. Now it’s very expensive for city agencies to build buildings.

That’s just not necessarily what they’re good at. When the private sector was

brought in, the city realized that they could get more housing built, do it

more efficiently and cost-effectively, and create units much more rapidly than

they could on their own. That said, it’s always a push and pull with the city.

As a private-sector developer, we’re making money on developer fees and cash

flow, and the optics of that can be a challenge, politically, for the city.

People are wondering, “Why are these private developers making money off of the

city?” In reality, we’re building buildings more effectively and efficiently

than the city would be able to do on their own. If it develops a project, the

city has to do it subject to all the public work rules that apply, which drives

up costs and timelines. In the private sector, we have an outstanding record of

delivering buildings on time, on budget, and safely.

With an increasing erosion of federal funding for public housing, do

you see housing authorities operating in a more entrepreneurial manner?

Housing authorities are already operating in a more entrepreneurial manner,

and that started at least five years ago, with the Rental Assistance

Demonstration Program (RAD). That program, initiated by the Department of

Housing and Urban Development (HUD), enabled housing authorities to bring in

private partners if they wanted to, or even finance buildings on their own.

With public housing contracts, it’s very difficult, if not impossible,

statutorily, to put debt on buildings. That’s a real challenge for NYCHA, which

has 170,000 units in various stages of disrepair and about $18 billion of

deferred maintenance. The only way that they’re going to generate enough

capital to renovate the buildings to a more sustainable standard is to partner

with the private sector and to use programs like RAD so that they can finance

their own buildings, generate capital, and reinvest either directly back into

the building they financed, or into their portfolio.

What stakeholders influenced the outcome of your joint partnership

with NYCHA? Did any political dynamic inform the outcome of the deal?

Whenever NYCHA partners with the private sector, there are a host of stakeholders

who become very skeptical. The mayor was on board and the various housing

agencies understood the urgency of the problem. But there was a whole other

cohort of stakeholders–residents, elected officials–who needed to be convinced.

So NYCHA spent a long time getting those people on board, assuring the

residents that there would be no rent increases or evictions. It was an

educational and outreach process.

Image of Saratoga Square, one of the developments undergoing partial privatization

The six sites are located in a wide array of neighborhoods.

Presumably this makes each project quite unique, not only financially, but also

politically. Can you speak to this variation?

Each property is subject to three levels of public involvement. First, the

residents and the tenant association (TA) president. Then the local

councilperson. From there, you have the bigger picture: the chair of the Public

Housing Committee of City Council, the Committee itself, and the Speaker. So in

each case, there were different concerns. The residents’ concerns were related

to the specific building. The elected official’s concerns related to the

specific climate of the City Council district. And then, on a broader scale,

the City Council committee raised issues on transparency, long-term

affordability and so forth.

In the East Village, at a property named Campos, it was a challenge to get

the local elected official on board, while residents and resident leaders were

in support of the deal. There’s a lot of development going on in the

neighborhood, and local residents are being displaced. The council-person was

skeptical that we might come in and build condos there, even though we can’t do

that without NYCHA’s permission. But because of what was happening in that

council district, the council-person was very protective. Anything that she

could have a say in, she was clamping down on.

Compare that to the property in the Bronx, where we had a TA president who

was very skeptical, and a local elected official who was less vocal against the

transaction. She knew L+M, knew what we had done in the past, and understood

the necessity of the transaction from a security and sustainability

perspective. In the Bronx, there was less concern that we were going to convert

the buildings to market-rate condos.

Can you explain how NYCHA will benefit from the partnership?

NYCHA will receive a series of payments. They received a partial payment of

the purchase price when we closed on the financing of the property. Then when

we stabilize the properties and convert to the permanent phase of financing,

they’ll receive the rest of the purchase price. They’ll also benefit from a

portion of the developer fee and ongoing cash flow. So, NYCHA’s received a big

payment up front that they’ve already reinvested into other properties and used

to close their budget gap for the first time in many years.

The transaction itself enabled the buildings to be renovated with about $80

million worth of hard cost, and NYCHA to take $250 million in purchase price

and put it back into their budget for whatever they see fit. We did that by

leveraging the mark-up-to-market HUD contracts, and using debt and tax credit

equity to combine into the financial structure for the deal.

From an ongoing perspective, NYCHA will receive half the developer fee and

then three quarters of the cash flow. There’s also a seller’s note that they

will be paid on. So there are a number of different buckets of proceeds that

NYCHA will receive, and they’ll be able to use it however they wish.

What kinds of “reasonable cause” can NYCHA cite to cancel the

contract with L+M and BFC? And what is the nature of the 30-year opt-out clause

governing the buildings?

NYCHA has a number of different rights in the joint venture. They are the

ultimate decision-makers in basically everything. We can’t sell the property;

we can’t convert to condos; we can’t really do anything without NYCHA signing

off on it. And we have no interest in doing that with these properties. Through

the deal we are receiving HUD contracts, which are very valuable and pay market

rents. NYCHA has a purchase option in 15 years and can take back the properties

if they want to. And then, at the end of the 30-year affordability period,

NYCHA is the ultimate decision-maker. They decide what happens at that point.

Most likely, we will do a similar transaction and extend the affordability

further.

Do you see this deal as providing a clue to the future of affordable

housing in New York?

We see this transaction as a model for the potential of public housing. We

can generate proceeds that NYCHA can use to reinvest in their portfolio. We

renovate their properties and manage them. And we do all of that in a more

efficient and effective manner than NYCHA can. It’s a public-private partnership

and a real joint venture with NYCHA in which NYCHA has decision-making

capability and can leverage the strength of the private sector in terms of what

they’re good at doing: building and managing housing.

There’s a way to do that effectively and in a real partnership where the

residents feel like their interests are protected, and from our perspective,

we’re making money off the property, which gives us an economic incentive to do

the right thing and reinvest money into the property and operate it well. As

the property does better, we do better.

Adam Tanaka is a Ph.D. student in urban planning at the Harvard Graduate

School of Design and a Meyer Fellow at Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing

Studies. His research focuses on housing policy and development in the

contemporary United States, drawing from the fields of political science, law,

urban planning, and real estate to develop methods for understanding and

improving urban housing provision.

Many thanks to Jessica Yager at the Furman Center for Real Estate and

Urban Policy for helping to arrange the interview.

Read more in the Challenges to Democracy series, including Adam Tanaka's posts.

Read the opening post to this series, which we cross-posted in April 2015.