|

| by Jonathan Spader Senior Research Associate |

Discussions of the declining homeownership rate—which fell from 69 percent at its mid-2000s peak to below 64 percent in 2015—frequently point to demographic trends, such as delayed marriage and childbirth, an increasingly diverse U.S. population, and changing attitudes and preferences among both Millennials and retiring baby boomers, as the primary source of the decline. However, non-demographic factors like high foreclosure rates, tightening credit standards, and falling household incomes probably also contributed to the recent declines. To better understand the relative importance of the demographic changes, I used data from the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS/ASEC) for 1985-2015 to examine the extent to which changes in the distribution of U.S. households by age, race/ethnicity, and family type contributed to both the rise and fall in the homeownership rate over the past two decades.

I found that while there have been significant demographic changes in the last 30 years, these changes alone do not explain the last decade’s drop in homeownership rates. Nor do demographic trends explain why the homeownership rate rose from about 64 percent in 1990 to 69 percent in 2005. Rather, changes in the demographic profile of U.S. households suggest that the homeownership rate should have steadily declined by about 1-2 percentage points between 1985 and 2015. This, in turn, suggests that the rise and fall in the homeownership rate between 1985 and 2015 reflects changes in the broader economy, home price appreciation, mortgage credit conditions, and possibly household preferences for owning versus renting that alter the likelihood that demographically-similar households are homeowners.

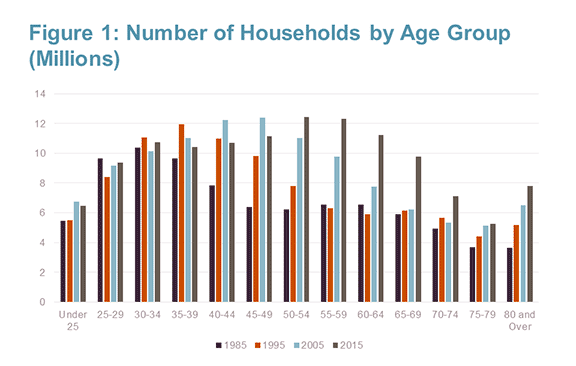

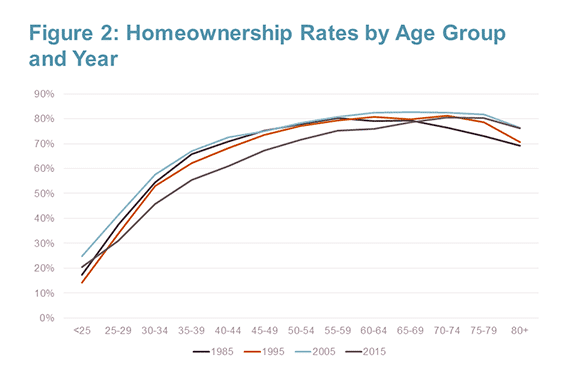

Several demographic trends are reshaping the profile of U.S. households. First, the aging of the baby boomer generation has increased the number of households in older age cohorts. For example, the number of households headed by an individual age 55-59 hovered near 6.5 million from 1985 to 1995 before increasing to 9.8 million in 2005 and 12.3 million in 2015. (Figure 1) This shift has put upward pressure on the homeownership rate by increasing the number of households in older age cohorts, which have higher homeownership rates than younger age cohorts. (Figure 2) In coming years, the baby boom generation will continue to reshape the profile of U.S. households as they reach the oldest age groups.

Second, the racial and ethnic makeup of U.S. households is changing. The share of white non-Hispanic households declined from 81.3 percent in 1985 to 67.6 percent in 2015. Over the same period, the share of black households increased from 10.8 percent to 12.5 percent, the share of Hispanic households more than doubled from 5.6 percent in 1985 to 13.0 percent in 2015, and the share of Asian and all other households more than tripled from 2.2 percent in 1985 to 6.8 percent in 2015. (Figure 3) The implications of these trends for the homeownership rate depend on whether historical differences in homeownership rates across groups will persist in coming years. Historical CPS data suggest that the Hispanic-White and Asian/Other-White gaps in homeownership rates narrowed only slightly between 1985 and 2015, whereas the Black-White gap increased from 24.6 percentage points in 1985 to 28.8 percentage points in 2015. (Figure 4)

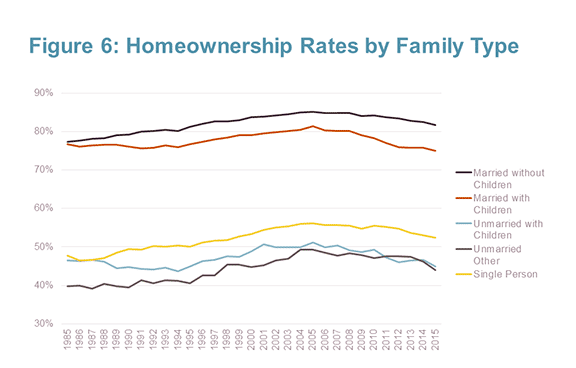

Third, larger numbers of young households are delaying marriage and childbirth until later in life, or forgoing them entirely. The share of households headed by a married couple decreased steadily from 58.9 percent in 1985 to 49.9 percent in 2015. The reduction is due entirely to decreases in the share of married couples with children, as the share of married couples without children remained approximately constant during this period. The decline is offset by increases in the share of single person households, unmarried households with children, and other unmarried households. (Figure 5) While homeownership rates for all groups have declined in recent years, the rates are consistently highest for married couples with children. (Figure 6)

To estimate the cumulative effect of these trends, I conducted shift-share analyses using the CPS/ASEC data. These analyses hold constant homeownership rates at their levels in various years to reveal the extent to which changes in the homeownership rate are driven by changes in the number of households in each age, race/ethnicity, and family type group. For example, using the 1985 sample, I calculated the 1985 homeownership rates associated with each combination of the 13 age groups, 4 racial/ethnic groups, and 5 family type groups shown in the figures above—creating 260 categories in total. For each of the years from 1986-2015, we can then calculate what the U.S. homeownership rate would have been if the homeownership rates for each group remained at the 1985 level. (Readers seeking a more detailed description of the methodology for this analysis can consult a forthcoming JCHS working paper.)

Figure 7 displays the results of such calculations when rates are held constant at their levels in 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. The projected homeownership rates suggest that changes in the profile of U.S. households by age, race/ethnicity, and family type do not explain the boom and bust trends in homeownership rates since the early 1990s. Rather, these factors predicted a modest decline in the homeownership rate of about 1-2 percentage points between 1995 and 2015. However, the overall predicted homeownership level varies sharply across the various years, which is the result of unmeasured changes across time in the broader economy, home price appreciation, mortgage credit conditions, and possibly household preferences for owning versus renting that alter the likelihood that demographically-similar households were homeowners in different years.

For a second analysis, I added additional variables to the shift-share analysis using a regression model to calculate the homeownership rates associated with each variable. (Again, more detail about the methodology can be found in the forthcoming working paper.) Specifically, the second analysis adds information on household income, employment status of the head and spouse, educational achievement, veteran status, and more detailed measures of marital status and the presence of children in the household. The projected homeownership rates from this analysis show that while these factors produce more volatile projections, they explain very little of the rise and fall in the actual homeownership rate between 1985 and 2015. The one possible exception is the period from 1996 to 2000, when rising incomes and employment help to explain a portion of the rise in the homeownership rate at that time. However, these factors are not able to explain the continued rise of the homeownership rate following the 2001 recession or the subsequent bust in the latter part of the decade. (Figure 8)

Taken together, these findings suggest that demographic factors explain very little of the rise and fall in the homeownership rate from 1985-2015. Rather, changes in the profile of U.S. households during this period have placed competing pressures on the homeownership rate and largely offset one another. Looking forward, the aging of the baby boom generation and the coming of age of the Millennial generation are similarly unlikely to substantially alter the homeownership rate in the near future. Instead, the trajectory of the homeownership rate depends more heavily on how quickly the foreclosure backlog clears, how many people who lost their homes to foreclosure buy homes in the future, how long mortgage credit conditions remain tight, and whether young households’ slowed rates of homeownership entry persist in future years. Additionally, any major changes in the broader economy, housing finance system, or attitudes toward homeownership may also influence future homeownership rates to the extent that they alter households’ demand or access to homeownership.

This is well thought out for developed countries but for most developing nations, the major factors are poor governance and corruption... combating this factors in such contours is a major research area scholars need to work on, for example .. creation of frameworks that will reduce the effect of corruption on social housing delivery

ReplyDelete