|

| by Michael Carliner Senior Research Fellow |

Notes: Data for 2013, except Canada 2011

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Housing Survey; Statistics Canada, National Household Survey; Eurostat, European Union Survey of Income and Living Conditions

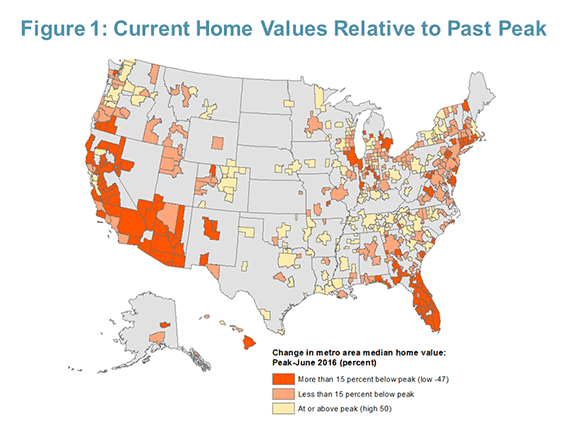

Figure 1 shows the twelve countries we included. The share of all households who were paying rent in 2013 ranged from 15 percent in Spain to 59 percent in Switzerland. The 33 percent share in the US was in the middle of the range and similar to several other countries. Some non-homeowning households were living rent-free, generally because of their employment or relationship to the property owners. Such rent-free occupants represent a small share of households in the US and most other countries, but account for more substantial shares of households in Italy, Spain, and Austria.

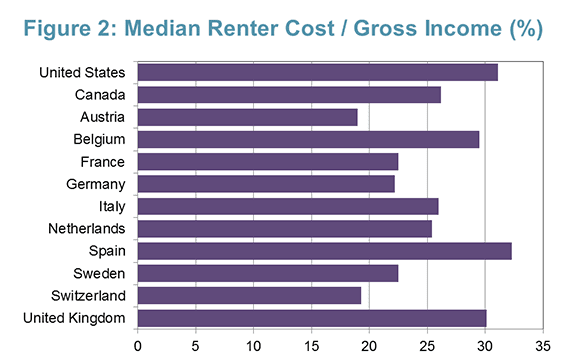

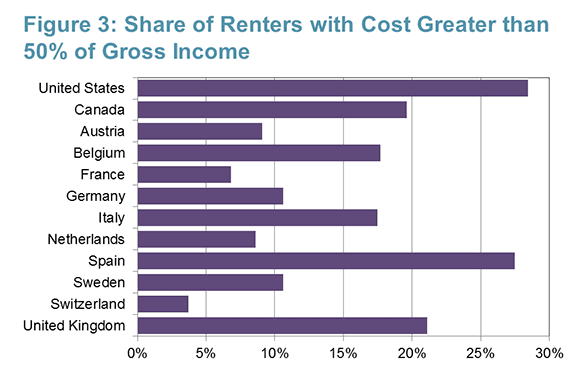

Comparing rental markets in the twelve countries revealed that the US was exceptional in a number of (often unfavorable) ways. The median ratio of housing cost to household income (Figure 2) was greater in the US than in any of the other countries studied, except for Spain, where there are relatively few renters. Moreover, the share of renters with severe cost burdens — paying more than 50 percent of their income for housing — was greater than in any of the other countries (Figure 3.)

Notes: Data for 2013, except Canada 2011

Other exceptional characteristics of renter households in the US included an average household size of 2.39, which is greater than in any of the other countries, except Spain. The share of US renter householders aged 65 or over (12.1 percent) was less than in any of the other countries, again with the exception of Spain. Also, the share of renters living in single-family detached houses was much higher in the US compared to the other countries.

In many other respects, rental housing in the US was not exceptional. While the median living area and number of rooms in US rentals is greater than in most of the other countries, several countries had comparably-sized rental units, especially after adjusting for the number of occupants. (This is in contrast to owner-occupied housing, where units in the US tend to be substantially larger than those in other countries.)

In all of the countries studied, foreign-born householders were more likely than native-born householders to be renters. In the US, 14 percent of all householders, and 20 percent of renters were foreign-born. The foreign-born share of all householders ranged from 7 percent in Germany to 38 percent in Switzerland. The foreign-born share of renter householders was more than 45 percent in Spain and Switzerland.

In each country, lower income households were more likely to be renters than those with relatively high incomes. In the US, about 33 percent of renter households were in the lowest quintile of the income distribution. In six of the other countries, the share of renters in the lowest income quintile were greater than in the US, so the US did not exhibit unusual concentration of rentership at the low end. Because of greater overall income inequality in the US, however, households in the bottom quintile had lower incomes, relative to the national median. Indeed, the median income of households in the bottom income quintile in the US (the 10th percentile) was 24.5 percent of the overall median household income, while among the other countries that ratio ranged from 27.9 percent to 39.1 percent.

Much of the focus of our analysis was on affordability and on the reasons why it is a greater problem in the US than elsewhere. The degree of income inequality is one factor. Another important influence on renters' cost was the availability of housing allowances, known in the US as vouchers. Although US renters with vouchers are provided with fairly generous subsidies, only a small share of renters actually receive vouchers. In France and the UK, about half of all renters benefit from housing allowances. In the Netherlands, Sweden, and Germany, as well, large shares of renters receive housing allowances. Our analysis shows that the effects of housing allowances on affordability are substantial in those countries.

Although affordability in the US is typically measured by comparing housing cost to gross (before-tax) income, in Europe it is common to look at housing cost relative to disposable (after-tax) income. On that basis, the median ratios of housing cost to income for renters in Belgium, the Netherlands, UK, and Spain, were higher than in the US, where taxes are lower. But the share of renters with severe cost burdens (greater than 50 percent of disposable income) was still greater in the US than in every country except Spain.

While the objective of the paper was largely to provide comparable statistics regarding the characteristics of renters and the rental housing stock in a number of developed countries, it underscores the severity of rental housing affordability problems in the US. It doesn't provide a clear answer to the question of how to improve affordability in the US, but it does suggest where to look.

Read the working paper.

Read the working paper.