|

| Irene Lew Research Analyst |

In the early 1970s, in response to growing concerns about

the housing conditions of poor families, the US Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD) developed a measure of housing adequacy for its American Housing Survey (AHS)

that continues to be used by the agency today. This adequacy measure was originally designed to evaluate the extent to which the national housing stock met the

standard of “a decent home and a suitable living environment” established by

the Housing Act of 1949. While the condition of the housing stock has improved

over the past several decades, the rental stock is still three times more

likely than the owner-occupied stock to be considered inadequate. And problems

persist among the most affordable rentals.

While fairly complex, the AHS adequacy measure factors in

various housing problems related to plumbing, heating, electrical wiring, and

maintenance. Using this AHS measure, the majority of the nation’s rental

housing stock is in physically adequate condition. As of 2013, just 3 percent

of occupied rental units were categorized as severely inadequate and 6 percent

were moderately inadequate. In fact, the adequacy of the rental stock has

improved over the past decade, with the share of rentals categorized as

physically inadequate declining from about 11 percent in 2003 to 9 percent in

2013.

Notes: Inadequate units lack complete bathrooms, running water, electricity, or have other deficiencies.

Source: JCHS tabulations of HUD, American Housing Surveys.

Stricter building codes have certainly helped to encourage

higher quality, particularly the construction of units with complete plumbing

and heating systems. As a result, severe physical deficiencies have been rare

among the rental stock, especially among newer rentals. Just 1 percent of rentals

built 2003 and later was classified as severely inadequate, compared to 4

percent of those built prior to 1960.

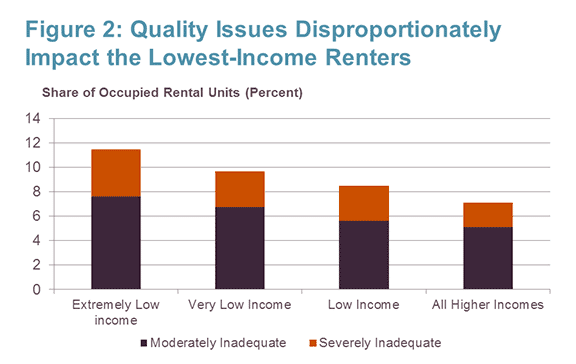

It is noteworthy, however, that the AHS adequacy measure

does not account for certain health-related quality issues such as the presence

of mold or structural issues such as holes in the roof or foundation, so housing

quality problems may in fact occur at higher rates than the survey reports. And

although physical deficiencies have become less common among the nation’s

rental housing stock, housing problems disproportionately appear in units

occupied by the lowest-income renters. In 2013, 11 percent of units occupied by

extremely low-income renters (those with incomes less than or equal to 30

percent of area medians) were physically inadequate, compared to just 7 percent

of those with incomes above 80 percent of area medians.

Notes: Extremely low / very low / low income is defined as up to 30% / 30–50% / 50–80% of area median income. Inadequate units lack complete bathrooms, running water, electricity, or have other deficiencies.

Notes: Extremely low / very low / low income is defined as up to 30% / 30–50% / 50–80% of area median income. Inadequate units lack complete bathrooms, running water, electricity, or have other deficiencies.

Source: JCHS tabulations of HUD, 2013 American Housing Survey.

The lowest-income households also accounted for the largest

share of renters reporting overcrowded conditions and physical housing problems

such as toilet breakdowns, exposed electrical wiring, heating equipment

breakdowns lasting six hours or more and the presence of rats in the unit.

Notes: Extremely low / very low / low income is defined as up to 30% / 30–50% / 50–80% of area median income Overcrowded conditions refer to units where there are more than two people per bedroom. Holes in the floor are those that are about four inches across.

Source: JCHS tabulations of HUD, 2013 American Housing Survey.

Matthew Desmond’s most recent book, Evicted, vividly captures these statistics, drawing attention to the grim housing conditions of families in low-rent units in inner-city Milwaukee who must live with the constant presence of roaches and other vermin, clogged sinks and bathtubs, holes in their windows, and broken front doors.

Rentals occupied by extremely low-income households in

central cities have the highest physical inadequacy rates, especially those located

in small multifamily buildings with 2-4 units. Indeed, 16 percent of these

units were categorized as inadequate, compared to 12 percent of those in

buildings with 50 or more units. As I pointed out in a previous post,

small multifamilies are a critical source of low-cost housing because they tend

to charge lower rents than those in much larger structures, but much of this

stock is rather old and at higher risk of loss from the affordable stock due to

deterioration.

As this recent NPR piece suggests, the narrow margins for mom-and-pop landlords operating in

low-income neighborhoods do not provide sufficient incentive for landlords to make

improvements or repairs in a timely manner. Indeed, according to the American

Housing Survey, 13 percent of extremely low-income renters reported in 2013 that

the owner of their unit usually did not start major repairs or maintenance quickly

enough, compared to less than half that share (6 percent) among higher-income

renters with incomes above 80 percent of area medians.

The prevalence of housing deficiencies among units occupied

by the lowest-income renters highlights the importance of bolstering building

code enforcement efforts at the state and local levels. However, municipalities

are often faced with tight budgets that lead to dwindling code enforcement

teams. Indeed, according to one estimate

in 2013, Cleveland and Detroit, among others, have cut their code enforcement workforce

by about half since the middle of the last decade. Cities like Baltimore,

Portland, and the San Francisco Bay Area are also facing shortages of building inspectors that make it difficult to deal with building code

violations. While increased code enforcement can identify landlords who are failing

to maintain their properties, this could also lead to unstable housing

situations for current tenants. Renters may withhold rent or call local

building inspectors as a tactic to push landlords to make necessary repairs, but

this could lead to eviction threats or the initiation of a formal eviction

process due to nonpayment of rent.

At the federal level, budgetary constraints have also

impacted efforts to address the physical deficiencies among the aging public

housing stock, which was largely built before 1970. Federal appropriations for

the public housing capital fund fell by 34 percent over the past decade and HUD

is faced with an estimated backlog

of $26 billion in capital maintenance and repairs (as of 2010). HUD’s housing

choice voucher and project-based rental assistance programs, which subsidize

rentals for low-income households in the private market, require landlords to pass

annual or biennial inspections for housing quality. However, the public housing

stock is not subject to regular inspections and has largely been prohibited

from using private capital to finance capital needs and repairs. As a result, compared

to other types of assisted rentals, physical housing problems are more common

among the public housing stock. In 2013, over half (53 percent) of public housing

units had more than two heating equipment breakdowns lasting at least six hours

and 13 percent of units had water leaks due to equipment failures within the

previous 12 months.

Living in unsafe, physically inadequate housing can lead to

adverse health and developmental outcomes for low-income families. Indeed,

recent research

confirms that children exposed to defects such as leaking roofs, broken

windows, rodents, and nonfunctioning heaters or stoves were more likely to

experience emotional and behavioral problems. Among five housing

characteristics studied—quality, stability, affordability, ownership, and receipt

of housing assistance—poor physical quality of housing was the most consistent

and strongest predictor of emotional and behavioral problems in low-income

children and adolescents. Poor housing conditions such as mold, chronic

dampness, water leaks, and heating, plumbing, and electrical deficiencies, are also

associated with health risks like respiratory illness and asthma. These

findings underscore the urgent need for cities to prioritize code enforcement

and work collaboratively with nonprofit tenants’ rights groups to deal with

landlords who are not responsive to requests for necessary repairs.

No comments:

Post a Comment