|

| by Shannon Rieger Research Assistant |

A substantial number and share of older Americans are living

in “multigenerational” households, according to our analysis of recently

released 2015 American Community Survey (ACS) one-year population estimates. In total, 20.3 percent of all non-institutionalized

adults aged 65 and over – about 9.4 million people – live in multigenerational

households that include at least two generations of adults (individuals over

the age of 25). The ACS data also show large differences in the prevalence and

composition of multigenerational homes by age, race, and ethnicity.

The new data not only reflect the fact that there are a

growing number of older Americans, but also that the share of older Americans

living in multigenerational homes has been growing steadily since the 1980s. These trends are likely to continue as baby

boomers age. Importantly, multigenerational living might allow some older

Americans to enjoy a higher quality of life while aging in place, as an

overwhelming majority of people want to do. At the same time, for some families of limited

means, multigenerational living may be a financial necessity rather than a

desirable living situation. Regardless

of why they are choosing multigenerational living arrangements, providing

families with education and support to suitably modify their homes could help these

arrangements be as safe, effective, and beneficial as possible.

Who Lives in

Multigenerational Homes?

About two-thirds of the 9.4 million older adults living in

multigenerational homes live in households that have exactly two adult generations

(usually parents and adult children aged 25 or older). The rest are in three-or-more-generation

households that typically include grandparents, adult children, and grandchildren.

Trends in

multigenerational living also change with age (Figure 1). The share of people living in multigenerational settings

is highest for individuals in their late 20s (mostly due to adult children

still living at home), then drops for those in their 30s as young adults move

out and form their own households. The share rises again for people in their

early 40s until peaking at about 23 percent for people in their late 50s. This “sandwich” age group includes people who

are living with their adult children, those who are living with their aging

parents, who often need daily support and care, and those living with both their

children and aging parents.

Notes: Multigenerational households are those with least two adult generations aged 25 or older or that include grandchildren, adult children, and grandparents. Householders and parents are considered “adults” regardless of age. Other household members include extended family members (e.g. aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews) and unrelated individuals. Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2015 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

Because adult

children move out and elderly parents pass away, the share of people living in

multigenerational households declines for people who are in their 60s and early

70s. However, the share rises steadily for older adults in their mid-70s, who

often are starting to face more daunting health and financial challenges. Among

the oldest age groups (aged 85 and over), 27 percent – about 1.5 million people

– lived in multigenerational households in 2015.

In addition to

differences in age, people of color and foreign-born individuals are far more

likely to live in multigenerational settings than non-Hispanic whites and

people born in the United States (Figure

2). More than 25 percent of native-born blacks, Hispanics, and

Asians/others aged 65 and over live in multigenerational homes, as do more than

45 percent of foreign-born in all three of these groups. In contrast, 15

percent of native-born non-Hispanic whites of the same age, and just over 20

percent of foreign-born non-Hispanic whites, live in multigenerational

households.

Notes: Whites, blacks, and Asians/others are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race. Multigenerational households are those with least two adult generations aged 25 or older or that include grandchildren, adult children, and grandparents. Householders and parents are considered “adults” regardless of age.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2015 American Community Survey 1-year Estimates.

A sizeable subset

of these multigenerational homes include at least three generations: usually grandparents,

adult children, and grandchildren living together under the same roof. Roughly

ten percent of native-born blacks, Hispanics, and Asians/others aged 65

or over live in such households, along with around 25 percent of foreign-born

older adults in each group. Among non-Hispanic whites, just under 4 percent of

older native-born adults and 7 percent of the foreign-born live with three or

more generations.

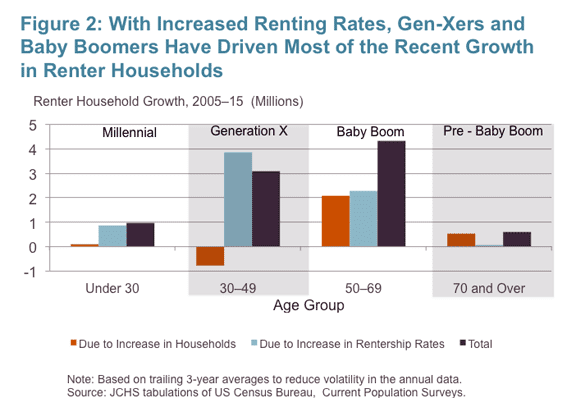

Looking forward, projected growth and demographic shifts in

the older population seem likely to increase the number of multigenerational households

and the share of people living in those households. The U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent population projections estimate that by 2035, about

79 million Americans will be age 65 or older, an increase of more than 30

million people in just two decades. This

growth is due to the fact that the baby boom generation is getting older and

because with increases in longevity

more people will live well into their 80s, 90s, and beyond. In fact, the Census Bureau projects the

number of “oldest old” adults aged 85 and over to double over the next two

decades.

The racial and ethnic composition of the older population

will also shift markedly over the next several decades. The non-Hispanic white

share of the 65-and-over population is projected to drop nearly ten percentage

points to 69 percent by 2035, while the black, Hispanic, and Asian shares will

rise, respectively, by 20 percent, 67 percent, and 39 percent (Figure 3). Census Bureau projections

estimate that the foreign-born share of the 65 and over population will also

continue to increase, growing from 13 percent in 2015 to 19 percent in 2035. Though

the direction of future residential preferences among the older population is

uncertain, the sheer magnitude of growth in the older population and the fact

that much of the growth will be among the very old, people of color, and the

foreign born suggests there will be substantial growth in multigenerational

households in the coming years.

Notes: Whites, blacks, and Asians/others are non-Hispanic. Hispanics may be of any race.

Source: JCHS tabulations of US Census Bureau, 2014 Population Projections.

Impacts on Housing

and Services

As this growth occurs, it will be important to consider how

new and existing housing stock might be designed or modified to best meet the

needs of multigenerational households. Universal design features including single-floor living, zero-step entrances, and hallways and doorways wide enough to

accommodate wheelchairs, walkers, or strollers can make homes more accessible

for older adults with mobility limitations as well as for their young

grandchildren. Flexible layouts that can change as family needs evolve, as well

as the addition of semi-private spaces for each generation (such as in-law

suites with separate entrances, multiple master bedrooms or kitchens, and

accessory dwelling units), can also help make the housing stock better suited

for multigenerational households.

While multigenerational living works well for many households, it is important to note that it is not

necessarily a desirable option for every family. Rather, multigenerational living may be a

financial necessity rather than an attractive housing option not only for

families with lower incomes but also for moderate-income families living in

higher-cost areas. Further, sharing a home with multiple generations can be challenging,

particularly if the house is small, has inadequate amenities, or there are

unclear or unrealistic expectations about responsibilities for both finances

and personal care. Finally, informal help from family members may not be an

adequate replacement for professional care, particularly for aging adults with

serious health conditions. Providing families with guidance about how to live

successfully in multigenerational settings, and, perhaps, with financial

assistance to make home upgrades and modifications, will therefore be critical if

multigenerational living is going to be an appealing, comfortable option for

families of all means. While designing and carrying out such policies and

programs will be challenging, such efforts have the potential to provide a more

appealing and cost-effective housing option for older Americans and their families.